“We spend 90% of the day indoors. The built environment has a great effect on our mood, mental state, and well-being. Spaces that are purely functional risk dehumanizing people. To design buildings that foster well-being, we have to focus on the people inhabiting them,” explains Anjan Chatterjee, a professor of neurology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He is also the director of the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics, which explores how aesthetic experiences like art and architecture affect our brain and behavior.

Just as engaging in art and culture can help us heal, the spaces we live in also affect how we feel. Aesthetic experiences constantly happen all around us. As Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross write in their book Your Brain on Art: “The light in the room, the sounds around you, the smells; these are aesthetics, as potent as a Picasso or a Rothko.”

This is especially true in places like mental health hospitals, where patients arrive at their most vulnerable. Many of these highly managed, functional spaces have bright lighting pouring down from overhead fixtures, the walls painted beige, the furnishings sparse. They feel unwelcoming, often lacking a sense of care.

As Chatterjee points out, our old brains are stuck in a new environment. They evolved during the Pleistocene, over the span of around 1.8 million years, in which we lived in natural environments. So it’s only in the last 10,000 to 12,000 years that we've been living in dense cities like New York.

This might explain why we feel more at ease in buildings that bring the outside in. Chatterjee is currently designing “refresh rooms” based on biophilic design principles for Alpas Wellness, a new mental health facility in Maryland. The idea is to create two spaces for patients and staff to see if this kind of environment has a positive effect on the regulation of their emotions.

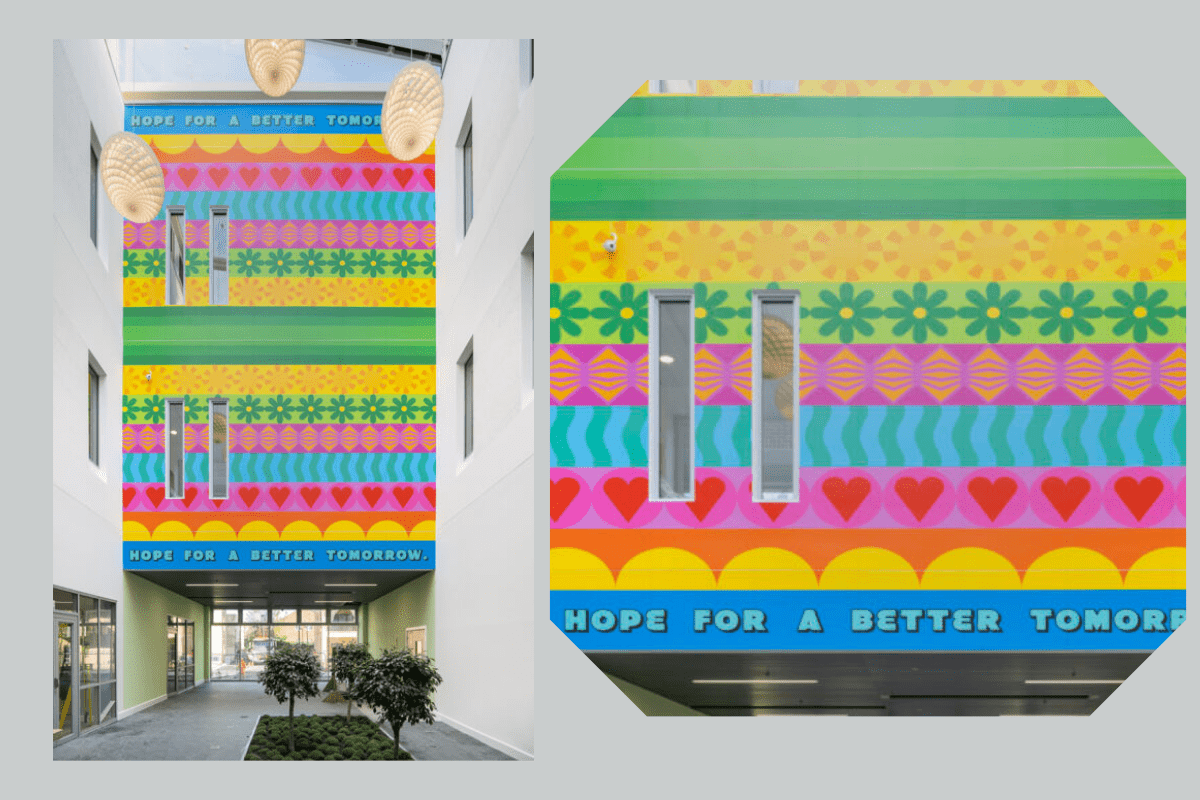

Hospital Rooms: Creativity, Care and Kindness

But what about publicly funded facilities with limited resources, many of which are several decades old? How can these functional-first facilities, often run-down, be cost-effectively transformed to promote wellbeing?

In 2016, artist Tim A Shaw and curator Niamh White asked themselves the same question after visiting a close friend who had been admitted to a mental health ward following a suicide attempt. They were shocked to find the hospital environment was “cold and clinical”.

Having worked over 10 years in the art world, the couple had the idea to leverage their experience and network to bring gallery-worthy artworks to inpatient mental health units across England.

But when they first approached NHS facilities, decision-makers were sceptical. It was considered too risky to bring outside communities into these highly secured spaces. Some even feared patients could vandalize the artwork, showing the stigma that can exist within the mental health system itself.

Today, almost 10 years and 200 artist commissions later, the majority of artworks are still there and in very good condition and Hospital Rooms has since received an overwhelming number of collaboration requests from NHS facilities.

Over the years, the nonprofit has brought world-class artworks by renowned artists such as Sutapa Biswas, Sonia Boyce, Nick Knight, and Anish Kapoor into mental health wards; along with a sense of dignity and imagination.

“When we start working on a project, we take a very nuanced approach, as every community and environment has different needs,” explains Haley Moyse Fenning, Hospital Rooms’ Head of Impact, in an interview with The Overview. “That’s why we begin with a research and development phase before starting with the participatory process. The findings then help inform which artists and artwork we would like to bring into the hospital community.”

A research method the nonprofit uses is called Photovoice. “We give patients disposable cameras and ask them to take pictures that mirror their experiences with the ward.

One example that really stood out to me was one patient who took photos of all the signage that told him what he couldn't do, things like, 'Please keep off the grass,' 'Don’t press this button,' 'Do not enter.' He built up this catalogue of restrictions through these visual pieces.

Then, we asked the patients to reimagine the space on top of the images they had taken. For example, with a white wall and a 'no entry' sign, we asked, 'What would you want to see here instead?' This process helps reveal new ideas.”

After the research and development stage, a three- to six-month co-production phase follows, featuring creative, artist-led workshops with the patient groups. The themes, ideas, and colors assembled in these sessions inspire the final artwork, ensuring that it reflects and evokes the experiences had in the workshops.

“One of my favourite examples is a beautiful, expansive atrium piece in Springfield Hospital, in South London. The mural titled “All around me, my gathered star” was created by conceptual artist Sutapa Biswas. She worked very closely with the patient group to identify the blue color and to think about themes around the stars.”

During the workshops the patients also created their own artworks. They learned about creative approaches, methods, techniques, and more directly from Biswas and had access to all the art supplies they needed.

“Patients also connect with each other in a space outside their normal routine to engage in creative activity. Then their ideas are being taken forward into an artwork that will live in perpetuity, and that others will be able to benefit from” says Haley.

Another crucial aspect for Hospital Rooms is measuring the impact of their work on both patients and staff. A method the nonprofit uses to track the transformation of the environment from beginning to end is called Visual Matrix. Before a project starts, a focus group mostly consisting of staff members is guided through the space given prompts that encourage them to come up with associations of the environment.

“We often hear in these sessions that the environment seems ‘dark,’ ‘uncared for,’ ‘dilapidated,’ and ‘lifeless.’ At the end of the project, we run through the same prompts and questions with the same staff to see how they perceive the space with the artworks in place. The new answers are very different and range from ‘It's come back to life,’ and ‘It's bright,’ to ‘We are seeing people have conversations in these spaces.’ This area that we heard nobody ever went into is now where patients take their visitors when they come in.”

In addition to measuring the impact a project has had, Hospital Rooms is currently also collaborating with scientists through the Hospital Murals Evaluation (HoME) project, a research initiative between NYU Steinhardt, CultuRunners, and the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe.

The project brings together a multi-country study approach with findings from Slovenia, New York, UK and Nigeria, where Hospital Rooms has found a second home thanks to the artist Nengi Omuku, who has been collaborating with the charity for several years. Inspired by the experience, she set up a similar organisation in Lagos, named Ona Iwosan (The Art of Healing).

“The purpose of the HoME study is to examine the impact of murals within hospital settings across multiple countries and various healthcare communities for a broader understanding of the effects of art in different cultural contexts. The outcome from this research will be published in Autumn this year, however, first findings show that the participatory element is very important. Real impact occurred when patients or hospital communities had the opportunity to contribute to the mural in some way, which was very validating for us.”

The Crucial Role of Research

Architects and designers could benefit from Hospital Rooms’ approach to iterative research, in adapting the built environment to better meet the needs of its inhabitants.

As Chatterjee points out, many architects make prediction errors. They try to imagine how people will feel and behave in the spaces they design, but little research is done to verify whether their assumptions were correct, as feedback is rarely collected once the building is in use.

“For neuroarchitecture to mature and have a solid foundation, it needs to be grounded in research where people are doing experiments and not just saying, “This is how the visual system works” or “This is how spatial navigation works, and we should apply this idea to the built environment.” That’s fine, but the field will wear itself out in the long run if not animated by a robust research program.”