In the Hollywood Hills, at 2357 Hermits Glen, stands a mid-century house made of redwood and glass. It was once the home of Gene Loose, a professor of architectural design at the Chouinard Art Institute.

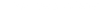

Here, far from the white-walled halls of the 2024 edition of Frieze Los Angeles, the house temporarily became a gallery presenting the works of French artist Cédric Rivrain. He often paints portraits of friends and acquaintances, and viewers can sense that intimacy in the eyes of his subjects, who stare directly back from the canvas. It was the artist’s first solo show outside of France, organized by Paris-based gallerist Robbie Fitzpatrick.

Word of mouth spread among fairgoers who decided to make the 30-to-50-minute drive from Santa Monica Airport. The show's success made Fitzpatrick realize, “This is how I want to represent my artists.” Burned out from the pressure of constantly programming exhibitions in his Paris location and the financial constraints of increasing overhead costs, in 2024 he decided to close his gallery at 123 rue de Turenne in Paris' Marais neighborhood to switch to a nomadic program of site-specific exhibitions worldwide. Since then, he has hosted shows at other select locations, including Maison Ozenfant, the first villa designed by Le Corbusier, and the Palazzo Carrozzini, a former tobacco factory in Puglia, Italy.

But even before changing to a nomadic model, Fitzpatrick already earned a reputation for organizing art events that blurred the boundaries between art fair, gallery exhibition, and public art. For example, in 2013, he launched Paramount Ranch in Los Angeles, an alternative art fair hosted at a former film set for Western movies.

In 2022, he co-founded the Basel Social Club, an annual counterprogram to Art Basel. Together with his co-organizers, artist Hannah Weinberger and curator Yael Salomonowitz, Fitzpatrick held last year’s edition on a farm outside of town. The New York Times covered the event and titled the piece "No one told the cows not to lick the artwork."

This year’s location was a former bank branch at Rittergasse 25, filled with artworks and performances around the theme “value, exchange and trade”, a fitting motto given the current news cycle on tariffs and trade wars. One piece that stood out was It’s a Whole Lotta Money by Harlesden High Street and Kendra Jayne Patrick, who installed a fully functional Black hair salon on-site.

To learn more about Fitzpatrick’s nomadic gallery approach, The Overview spoke to him by phone about his lessons learned, conservative trends in contemporary art, and the advice he gives to fellow gallerists.

You started your gallery business in 2013. What changes have you observed in the art world since then?

Robbie Fitzpatrick: One of the biggest shifts is the general increase in living expenses in cultural capitals all over the world. And that reflects directly on the operational costs of a gallery. Everything from rent to shipping, staffing, and travel has become more expensive.

Another major change is the globalisation of the art world. The amount of art fairs taking place in so many different parts of the world, and the expectation that galleries should participate in all of those new markets, is quite a drastic shift from when we first opened the gallery in 2013. Both Art Basel and Frieze have announced new additions to their global calendars in Qatar and Abu Dhabi.

One of the bigger players who closed his gallery in 2025 was Tim Blum. He spoke very candidly about the art fair fatigue he was experiencing and how he had lost the meaning in his work. Did he speak out about what many of his peers quietly felt?

Robbie Fitzpatrick: I felt burnt out and was operating at a pace that gave less attention to the experience of my audience and was more part of a system of consumption. I think this becomes particularly evident in places like the Venice Biennale. It's this mad circus where you compare notes with your colleagues. Everyone asks, "Have you done that pavilion?" or "Have you seen that show?" and it becomes a checklist to tick off. Even the wording mirrors that: "Have you ‘done’ that pavilion?" I see it as a symptom of today's information overload and consumerism.

Was that also the reason you shifted to a nomadic model? Or did that decision mature over the course of a few years?

Robbie Fitzpatrick: The idea actually goes back to the end of 2019, when the gallery still had spaces in both LA and Paris. My former business partner, Alex Freedman, decided she wanted to step away from the gallery, and this was right before the pandemic. So I made the decision to quietly pause operations, terminating the lease in LA and our original small space in Paris just to reflect on how I wanted to move forward. During those early days of lockdown I was already asking myself: do I actually need a permanent brick-and-mortar space?

I approached my artists and people around me, and almost everyone said “Don't do it– you need the space. People won't take a gallery operation seriously without a physical presence.” So going against my instinct, I signed the lease on a new space in Paris.

It was only after three years of operating there, when we were approaching the renewal of the rental agreement, that I stuck to my guns and decided to terminate the lease. I felt confident that I could do everything a gallerist is expected to do–primarily representing artists and making exhibitions–without having one fixed location.

You're a year into this now. How has your experience been so far?

Robbie Fitzpatrick: It's a matchmaking game. On the one hand I'm having a lot of fun filling a database with unique spaces all around the world where I would like to do shows. In some cases, the artists already have a space in mind where they’d like to exhibit. More often, though, I find the right location that couples perfectly with the body of work being made for the exhibition.

That’s not always easy. Once you find a location, you need to negotiate the terms with the landlord. So far, I’ve been quite lucky, as all of them accepted my proposals, but I'm sure eventually there will come a day when a location rejects my exhibition concept.

I’ve also found how important it is to have a local support network that can help with shipping, storage, and other logistical hurdles. After a year of doing this, I now have a group of different people on the ground–whether real estate brokers, interior designers, or architects– who can help make these projects possible.

Can you give me a rough idea of the cost difference compared to a brick-and-mortar gallery?

Robbie Fitzpatrick: It’s difficult to compare the two models directly because the cost structures are fundamentally different. With a permanent gallery, you carry fixed expenses every month, including rent, utilities, staffing, and insurance, whether there is an exhibition on view or not. These costs accumulate quickly and create constant pressure to keep programming, often at a pace that is not always healthy or strategic.

That pressure also leads to a lot of wasted spending. A permanent space requires you to fill a calendar even when the timing is not right. Not every exhibition sells well, yet you still have to invest in shipping, production, installation, communication, and staffing simply to justify keeping the space active.

With a temporary or nomadic model, costs are more concentrated and project-based. Each exhibition has its own budget, covering a short-term lease or location fee, transport, installation, and production. While some shows can be more expensive upfront than a single month of rent, you are only spending when there is a clear artistic purpose and an audience in place.

And how has engaging with collectors changed compared to before?

Robbie Fitzpatrick: I've reached new audiences because the shows have gained traction as compelling destinations that people are willing to travel to. That's been a great upside to this experiment. However, there is definitely the challenge of keeping collectors informed and abreast. There are still some who want to visit the gallery, and I need to remind them that I no longer have a physical space, so they’ll need to wait for the next show.

In general, I honestly never really liked working in the gallery all that much. I didn’t feel comfortable trying to convince collectors to attend a show when I sensed they weren't engaged with the content. I also noticed the rise of a new hustle mentality that also doesn't reflect how I want to work as a gallerist.

Now, with this new flexible model, I can announce that I’m doing a show with a particular artist in an interesting location for a set period of time. What I’ve noticed is that collectors respond very positively to that, looking forward to experiencing art in a richer context.

Sure, there were local collectors who were fans of my gallery and wanted to see every show, which is great, but there were also plenty who weren’t. I think this is something many galleries struggle with: how to keep the engagement consistent, not just with exhibitions in their own space, but also previews for fairs, offsite projects, museum shows and biennials involving their artists. That’s a huge amount of material to communicate, especially when collectors are receiving previews and invitations from dozens of galleries at once They're completely overwhelmed by the volume of content they're expected to engage with.

Does Basel Social Club also help reaching new audiences, for example younger collectors?

Robbie Fitzpatrick: I hope the social club model resonates with younger demographics because they can engage with art in a laid-back, informal setting. I feel that younger audiences have a lot of confidence in what they want. We have to meet them on their terms and social events can be a key entry point.

During Basel Social Club we also encourage dealers not to stand in front of the artworks they're presenting, allowing visitors to engage with the work at their own pace. We all know that experience of walking into a shop where an over-eager salesperson immediately approaches you and you just turn around and leave because you just wanted to browse on your own.

Live experience remains the best way to engage audiences. It's hard to get people's attention today, but when someone is in the same room with you, you can really connect. I've always believed that to do our job well, we have to spend time together, which is why art fairs still play an important role. They provide real opportunities for galleries to interface with collectors. That said, the format itself needs an update, especially when the status quo feels rigid or stuck.

Can you expand on that aspect? Where else does that play out in the art world?

Robbie Fitzpatrick: It's interesting because when we're talking about the contemporary art world that promotes freedom and new ideas, it's ultimately very conservative in how it clings to rigid definitions – how a fair should function, or how a museum should operate.

These models haven’t evolved, at all. The gallery model, in particular, is only now being seriously questioned. Even the way an artist is expected to operate in the studio is narrowly defined.

In which way?

Robbie Fitzpatrick: When I was in my early twenties, I didn’t go to art school, but almost all my friends were artists. At that time, if you were a young painter focused on still lifes of everyday objects–an apple or a pencil–you would have been dismissed outright. What I find surprising is that young artists today are embracing those subjects as a defining signature of their practice.

What do you think has caused this shift?

Robbie Fitzpatrick: I think there’s a degree of laziness involved. Still life has become a safe assignment—one with a long history, recognizable visual codes, and very little risk. It allows artists to produce work that’s immediately legible, aesthetically pleasing, and unlikely to offend or challenge anyone in a meaningful way.

What really sustains this trend is the market. Collectors are actively rewarding work that is quiet, domestic, and easy to live with. Soft color palettes, everyday objects, and a general sense of neutrality fit seamlessly into private interiors and require very little intellectual or emotional engagement. Unsurprisingly, they also sell extremely well.

This isn’t just about the market; it's about engagement and progress. Despite everything I'm also hopeful because these conventional models are beginning to fail– and that creates space for a broader paradigm shift.

What advice would you offer to emerging gallerists, or to those considering a transition to a nomadic model?

Robbie Fitzpatrick: My advice to any gallerist, whether pursuing a traditional brick-and-mortar or a nomadic approach, is to go about every exhibition in a very measured, intentional way. Squeeze as much as you can out of each show.

When I reflect on the pace of some of my previous projects, I wish I’d devoted more attention to each one instead of racing to the next or juggling them alongside art fairs. Now, when I organize exhibitions offsite in various cities, I take my time. And rather than just leaving immediately after the opening, I stay, immerse myself in the local community and build relationships.

When you leave, you haven’t just invested money–you’ve invested time and energy. And you come out feeling more culturally fulfilled.